Christian Zionism: made in America?

We recently drew attention to a version of Christian Zionism that calls itself “new.” Less apocalyptic and more academic than its older cousin. Less worried about Antichrist and more worried about antisemitism. Less a recent American innovation and more, it would seem, a return to ancient tradition.

It is too early to say whether new Christian Zionism will gain traction outside the academy, and whether it can become a force for peace and justice in the Holy Land.

Meanwhile, American-made, “old” Christian Zionism continues to hold sway in pulpits across the land of the free, and is even enjoying face time with the current U.S. president. Given its prominence and apparent influence in Washington, D.C. these days, it might be timely to review some history.

Back to the Garden: the hope of Christian Restorationism

Christians have long been zealous to see Jews return, or be restored, to Zion. Hymn writer Charles Wesley, inspired by Isaiah 66, penned these words in 1762:

We know it must be done, for God hath spoke the word

All Israel shall the Saviour own, to their first state restor’d

Re-built by his command, Jerusalem shall rise

Her temple on Moriah stand again, and touch the skies.Almighty God of Love

Wesley was hardly the first to believe in restorationism, the Christian idea that Jews would one day return to their land. Early Puritans, passionate for Scripture, likewise believed the Jewish people would be restored to their former glory (and come to name Jesus as Messiah).1

By the late 19th and early 20th centuries Christian restorationism was alive and well at the highest levels of British society. Three examples:

- Lord (Anthony) Ashley (Cooper), the 7th Earl of Shaftsbury (1801-1885): a philanthropist who urged Jews to move to Palestine. He wrote Prime Minister Aberdeen, published The State and the Rebirth of the Jews in 1839, and may be the one to have coined the phrase “a land without a people for a people without a land” in 1854 (in his diary).

- Reverend William Hechler: the chaplain of the British Embassy in Vienna (1845-1931) who lent Christian support to Jewish restoration, and introduced Theodor Herzl, the founder of Zionism, to the Grand Duke of Baden in 1896, and to his nephew, Kaiser Wilhelm of Germany, in 1898, seeking their aid in the Zionist cause. He believed the Jews of his day were fulfilling Biblical prophecy and regarded Herzl’s publication of The Jewish State as “a prophetic event.”2 Hechler attended first congress of the Zionist Organization in 1897 in Basel (Aug 29, 1897).

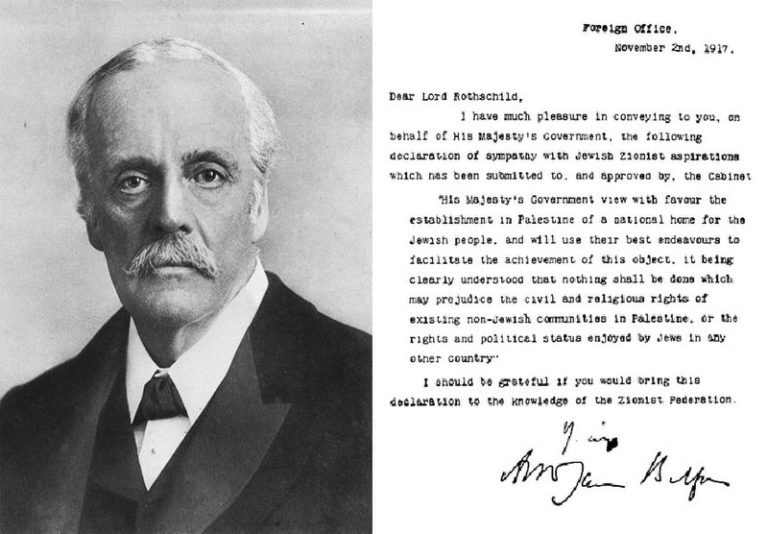

- Arthur James Balfour, the 1st Earl of Balfour (1848-1930): the British foreign secretary who believed a Jewish return to the land would fulfill prophecy. Influenced by the Zionist Chaim Weitzman and commissioned by Prime Minister Lloyd George, he wrote what became known as the Balfour Declaration of 1917, which begins like this:

“His Majesty’s government view with favour the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people, and will use their best endeavours to facilitate the achievement of this object. . .”

Scofield Bible in one hand, Newspaper in the Other

It was across the pond, however, where, in 1909, lawyer-turned-pastor Cyrus Ingerson Scofield (1843-1921) transcribed the hermeneutics of John Nelson Darby (1800-1882) into the footnotes of the King James Bible,3 thereby paving the way for homemade, American-style Christian Zionism. Darby’s dispensationalism was further popularized at prophecy conferences,4 taught at Moody Bible Institute, developed at Dallas Theological Seminary, marketed by Hal Lindsey, scratched into vinyl by Larry Norman, franchised by Tim LaHaye, projected onto the big screen by Billy Graham, and preached from pulpits across the land.

Thus, millions of American Christians learned that the children of Israel, long on God’s back-burner, could look forward to the restoration of their monarchy and even their resumption of sacrifice in a restored Temple.

For these Christians, the birth of Israel in 1948 was not simply a predictable outcome of the Ottoman Empire’s collapse. Nor did they see Israel’s establishment as merely a convenient solution to European antisemitism, much less as compensation for the Holocaust.5

On the contrary, what they saw was God’s Chosen Ones reclaiming centrality in the divine plan, which reclamation Darby and Scofield had seen coming because, well, they’d read their Bibles.

San Antonio megachurch pastor John Hagee sums it up nicely:

The rebirth of Israel as a nation was an unmistakable milestone on the prophetic timetable leading to the return of Christ.

In Defense of Israel (Frontline, 2007), 11.

Equally telling were the events of 1967 when Israel, now a teenager, went through a remarkable growth spurt. The swift victory in June of that year left Israel in control of Gaza, the Golan, the Sinai, the West Bank and, most importantly, East Jerusalem including the Old City and Temple Mount. For Dispensationalists, this was powerful vindication of their hermeneutic and its predictive power, as John F. Walvoord modestly professed in 1968:

The fact that Israel is now in their ancient land organized as a nation, and the impressive recent events which have put the city of Jerusalem itself into the hands of Israel, have to a large extent revealed . . . both the amillenarians and postmillenarians to be in error. To claim that this supports the entire premillennial interpretation may be presumptive, but it certainly gives added force to the normal interpretation of Scripture in predicting such a situation.

“Will Israel Build a Temple in Jerusalem?” BibSac 125 (498, 1968) 99-106 (citation pp.102-03).

Not only does the Bible help us interpret the morning paper. It turns out the morning paper has returned the favor.

From the Bleachers onto the Field

During the final decades of the 20th century—from Vietnam and the Six-Day War (1967) to the Gulf Wars (1991 & 2003) and 9-11 (2001)—or, in book-speak, from Late, Great Planet Earth (1970) to Left Behind (1996-2007)—a number of dispensationalist preachers descended from the hermeneutical bleachers onto the political playing field where they became increasingly engaged, media-savvy and influential.6

Some see this political turn as the true beginning of American Christian Zionism, in that conservative American Christians, driven by theological conviction, were becoming increasingly active in the political arena and increasingly vocal in support of the state of Israel. Indeed, the movement in America today is marked not simply by its hermeneutical confidence but also by its zeal for the nation-state of Israel and by political pressure to defend Israel against her critics.

The influence in the public square of those who claim to speak for God should interest all of us. More so when it shapes American foreign policy.7

What do Christian Zionists of this popular American variety believe about the Bible, about Israel and about current events in the Middle East? In my next post, I will attempt to summarize Christian Zionism in terms of seven basic claims.

You never know. I might be describing you.

- Paul R. Wilkinson, For Zion’s Sake: Christian Zionism and the Role of John Nelson Darby (Paternoster, 2007), 135-161; Victoria Clark, Allies for Armageddon: The Rise of Christian Zionism (Yale, 2007), 27-50. The term Christian Zionism appears to be of 19th century Jewish coinage. In 1896-97 Theodor Herzl used it of various Christian supporters of his nascent (Jewish-but-largely-secular) Zionist movement (Wilkinson, For Zion’s Sake, 16).

- Shalom Goldman, Zeal for Zion: Christians, Jews, and the Idea of the Promised Land (UNC, 2009), 88-136 (quote from p.105; see 93, 102-109).

- Oxford, 1909; rev. 1917 & 1967.

- Promoting Darby’s ideas were James H. Brookes (1830-1897) of St. Louis, Dwight L Moody of Chicago (1837-1899), William E. Blackstone (1841-1935) also of Chicago, and Arno C. Gaebelein (1861-1945) of New York. On their contributions see Clark, Allies for Armageddon, 85-92, and Wilkinson, For Zion’s Sake, 251-257.

- Gary Burge, Whose Land? Whose Promise? What Christians are not Being Told about Israel and the Palestinians (Pilgrim, 2003), 8ff.; Paul C. Merkley, Christian Attitudes towards the State of Israel (McGill-Queens, 2001), 161-162.

- Tracking this shift from observer to participant is Timothy P. Weber, On the Road to Armageddon: How evangelicals became Israel’s best friend (Baker, 2004), chapter 7, esp. pp.187, 196, 212. Merkley, Christian Attitudes, 163-183, provides a useful inventory of CZ organizations that emerged during this period. Cf. John J. Mearsheimer & Stephen M. Walt, The Israel Lobby and U.S. Foreign Policy (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2007), 133-34.

- Clifford A. Kiracofe, Jr., Dark Crusade: Christian Zionism and US Foreign Policy (Tauris, 2009). Kiracofe (pp.155-181); Clark, Allies for Armageddon, 176-283; Steven Zunes, “The Influence of the Christian Right in U.S. Middle East Policy,” in Naim Ateek, et al., Challenging Christian Zionism (Melisende, 2005),108-114. More cautious is Robert O. Smith, “Toward a Lutheran Response to Christian Zionism” (ELCA Conference of Bishops, San Mateo, CA, March, 2008), who warns against exaggerating the impact of Christian Zionists on American politics. Cf. Mearsheimer and Walt, Israel Lobby, 139.