Leave a Stone

According to the ancient Incas, spirits inhabit physical spaces—waterfalls, mountains, caves, rock piles. These energies are called huacas, a Quechua word for sacredness or holiness. High in the Andes today, the Inca posterity, villagers growing potatoes and quinoa or herding llamas and alpacas, maintain traditional rituals that revere as holy the sun, the moon and the mountains of the Pachamama, Quechua for Mother Earth.

Remove your Sandals

Sacred geography features prominently in Israelite tradition too, of course. When Jacob woke from his dream at Bethel, he exclaimed:

16 “Surely the Lord is in this place—and I did not know it!” 17 And he was afraid and said, “How awesome is this place! This is none other than the house of God, and this is the gate of heaven.” (Genesis 28, NRSV)

And God adjured Moses:

“Remove the sandals from your feet, for the place on which you are standing is holy ground” (Exodus 3:5, NRSV).

To this day, curious pilgrims to Mount Sinai may follow the guardians of St. Catherine’s monastery to the precise spot (!) where the Bush once burned. Transcendence lingers, in the imagination if not on the ground.

Stay off the Mount

Extra measures of holiness clung to Mount Sinai. In line with many ancient cosmovisions—Inca and Canaanite among them—Moses sought out the Transcendent One on a high place, where heaven touched earth. This mountain meeting with Yahweh on the land bridge between Africa and Asia would permanently orient the moral and ritual lives of the Israelites.

Sacred too was Israel’s wilderness tabernacle—like mountains, deserts were places of encounter—and the pair of Jerusalem temples whose localized sanctity was thought to linger long after their physical destruction. This residual holiness is why some rabbis today forbid Jews from ascending the Temple Mount; they don’t want the ritually impure transgressing the footprint of the holy sanctuary whose precise location, alas, is no longer certain.

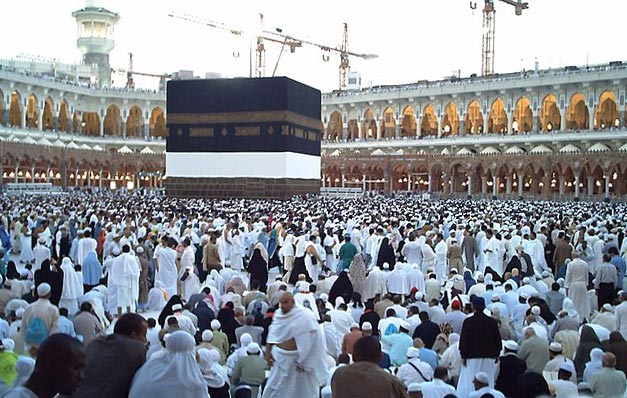

Muslims today encircle the Ka’bah, the sacred shrine in Mecca. Before COVID, 2.5 million made the annual Hajj pilgrimage. For centuries Muslims have also ascended to Jerusalem where the gilded Dome of the Rock dominates the skyline. In Arabic, the name for Jerusalem is simply Al Quds, literally “the holy [city],” a name that goes back, it seems, to the 10th century. 2

Return with Relics

The four Christian Gospels recount stories of an itinerant Messiah, not a sedentary philosopher. Matthew, Mark, Luke and John were not simply books of law and wisdom; the faith of their authors focused on a person who was on the move through space and time: down to a river, out to the desert, onto a mountain, out from a village, and up to Jerusalem. Thus, by the end of the 4th century Christian pilgrims to the Holy Land could fill up an itinerary with sacred destinations, and return with mementos—soil and stone, water and oil that retained and radiated the Land’s sacred power.

Sharing the path to Jerusalem with Jews and Muslims, Christians ascend to the holy city upon stones worn smooth from saints’ procession, stained by warriors’ blood, and etched with Crusader’s cross. The Holy Sepulchre Church itself, it seems, has become more holy over time, sanctified by overlays of stone, canvas and silver, purified by the footfalls and candle wax of saints and countless pilgrims.

Beyond Jerusalem, Christians leave footprints on holy ground wherever it may be found: Rome’s Vatican, Spain’s Camino, Mexico’s Basílica de Guadalupe, Scotland’s island of Iona, Greece’s Mount Athos.

Call No Place Holy

In the iconoclastic, low-church Christianity of my youth, we dared not ascribe spiritual properties to physical objects. That was what Roman Catholics did. So the unadorned concrete structure where we met (say, a rented gymnasium) was no sanctuary. It was merely a hall, the place where the church gathered weekly. No altar, icons or stained glass for us. No smoke, bells, robes or crucifixes. Just rows of seats surrounding the Lord’s Table, itself laden with a single loaf and a chalice of blood-red Port.

In our defense, we could quote Scripture. In the 4th Gospel, John has Jesus speak of his own body as the Temple.

19 Jesus answered them, “Destroy this temple, and I will raise it again in three days.” 20 They replied, “It has taken forty-six years to build this temple, and you are going to raise it in three days?” 21 But the temple he had spoken of was his body. (John 2: 10-21, NIV)

With Jesus, the locus of holiness was not a place but a person. Likewise, for Saint Paul, the community of Jesus-followers was holy because the Holy Spirit dwelled in the midst.

16 Do you not know that you are God’s temple and that God’s Spirit dwells in you? 17 If anyone destroys God’s temple, God will destroy that person. For God’s temple is holy, and you are that temple. (1 Cor 3:16-17, NRSV)

Saint Peter’s epistle (1 Peter 2:4-10) is on the same page.

Necessary but Dangerous?

My childhood suspicion of sacred objects and holy places was perhaps more Platonic than Christian. And more secular than religious. But if Christians have been localizing holiness since forever, we have been slow to recognize the paradox noted by Anglican academic C. S. Lewis: holy places may be necessary but they are dangerous.

It is well to have specifically holy places, . . . for, without these focal points or reminders, the belief that all is holy and ‘big with God’ will soon dwindle into a mere sentiment. But if these holy places . . . cease to remind us, if they obliterate our awareness that all ground is holy and every bush (could we but perceive it) a Burning Bush, then the hallows begin to do harm.3

The world I once knew, “big with God” but devoid of burning bushes, contrasts sharply with the sacrament-suffused, power-laden, Peruvian-Catholic world I now inhabit. Here, on festival days, crowds ascend to sacred shrines—to honor La Virgen or El Señor or the saint du jour, say Santa Rosa or Saint Martin de Porres—some folks unwittingly blending Christian devotion with Incan reverence, a syncretism of Latin veneration and ancestral earth worship.4

Profane but Sacred?

Less foreign to my senses, oddly enough, is the anomalous world of secular holy space. Were not the beaches of Normandy sanctified by the blood spilled on D-Day? Is not Ground Zero in lower Manhattan forever hallowed? Even the most secular soul must admit to a lingering, if merely inherited, sense of the sacred; religious folk do not own the monopoly. Historian of religion Mircea Eliade observed that “to whatever degree he may have desacralized the world, the man who has made his choice in favor of a profane life never succeeds in completely doing away with religious behavior.”5

Rim of the waiting earth

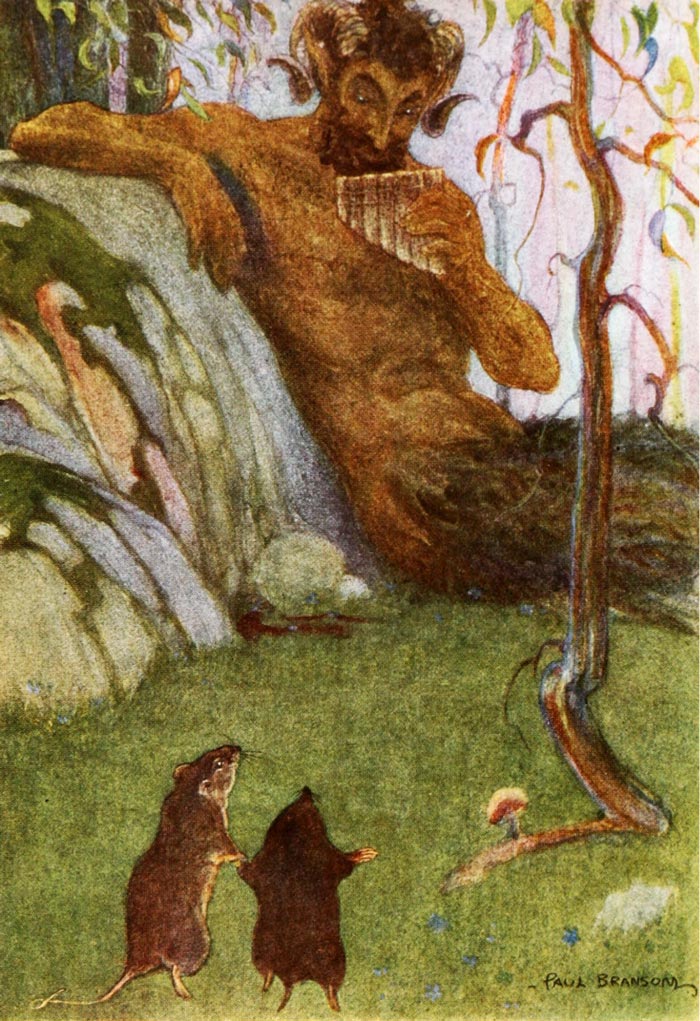

If you grew up with Kenneth Grahame’s novel, The Wind in the Willows, you may remember that Water Rat lives by the river and owns a boat. Early in the story Ratty and his friend Mole share a meal, in “the coolness of the riverbank,” to quote Van Morrison, “and the whispering of the reeds.” Ratty spends the evening telling stories, much like the river itself which forms “a babbling procession of the best stories in the world, sent from the heart of the earth to be told at last to the insatiable sea.”

Ratty and Mole later spend an anxious night sculling the river and scouring its banks for young Portly, the wayward and defenseless son of their friend Otter. It was a night “full of small noises” and blackness until, “at last, over the rim of the waiting earth the moon lifted with slow majesty till it swung clear of the horizon and rode off.” The moon cast its spell: meadows, gardens, the river itself “all washed clean of mystery and terror.”

Moment of Transcendence

As dawn approaches, Ratty recognizes distant pipe music. A melody rises within him, pleasing yet strange. Alas, his friend Mole hears only wind in the reeds. Ratty guides the boat toward the source. Mooring the vessel and scampering ashore, they find themselves forthwith in the presence of the Piper—god of the Wild—instrument in hand, with kindly eyes, curving horns and scruffy beard. Between his feet lies Portly, their lost friend, safe and sound asleep. The place was holy, the moment sacred, the encounter breathless.

Then follows a second wonder. A breeze rising from the water’s surface touches our two creatures, bathing them in oblivion. Ratty and Mole receive the gift of forgetfulness lest so haunting a moment “should remain and grow, and overshadow mirth and pleasure” and prevent them thereafter from cherishing the little things, the lesser moments of Transcendence that each day may bring.

No Longer Luminescent

Sometimes daybreak finds me paddling on river diamonds conjured by wind and sunlight. Other times currents ferry me toward reefs and shadows. Once in a while, without warning, I hearken to a melody and seek its source. But the Piper’s song, unbidden, does not linger. Holiness arrives, hovers, dissipates. My mortality cannot abide too much Transcendence.

No sooner had Moses faced the Piper on holy Sinai than he had to descend into a profane valley of people deaf to the music and wayward in worship. So too Jesus and his friends could not set up camp on the Mount of Transfiguration. No longer luminescent, Jesus descended to a lusterless world of demons, suffering and unbelief.

For me, perhaps for you, holy places are the exception to the mundane rule; moments of localized enchantment are real but rare. If that is so, let us go about our days cherishing simple gifts and smiling when melodious strains rise above the clangor. Is there not sanctity in a word of kindness, in deeds of compassion, in smiles of contentment, in acts of generosity? Do we not sense the sacred in a friend’s counsel, observe the holy in a companion’s delight, and recognize eternity in the face of a child?

Fading Sanctity?

Attentive travelers return from every trek with questions about sacred geography. I wonder whether places can be objectively holy, or whether all depends upon the imaginative disposition of the pilgrim.

Are holy sites discovered or constructed? Do art and architecture, do words and rituals, create holy space? Or do they embellish what is holy already?

Why do some spaces seem to grow in sanctity over time, as one generation of pilgrims follows another, while in other places, sanctity seems to fade as time nudges a holy moment or saintly person further into the past?

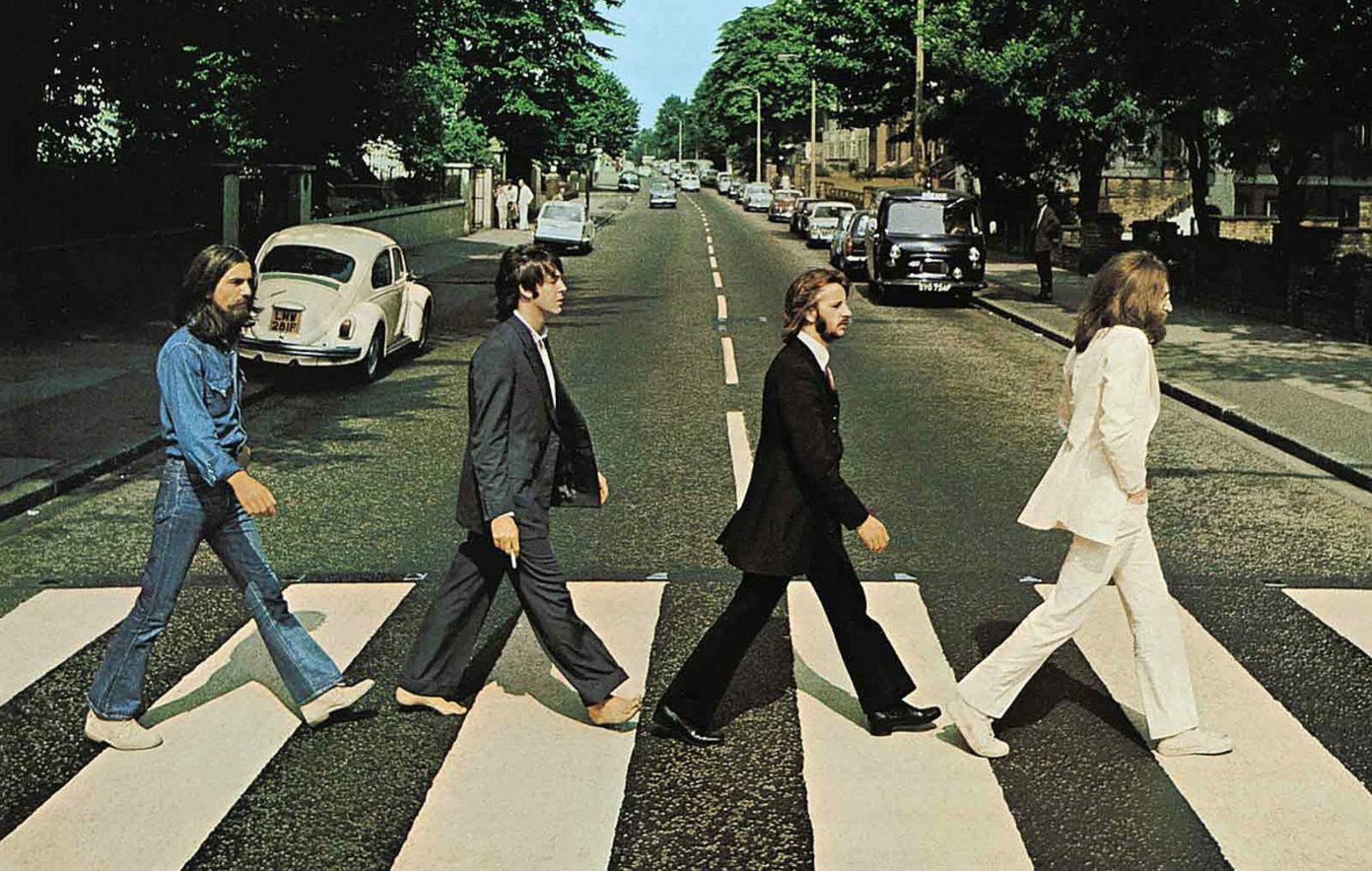

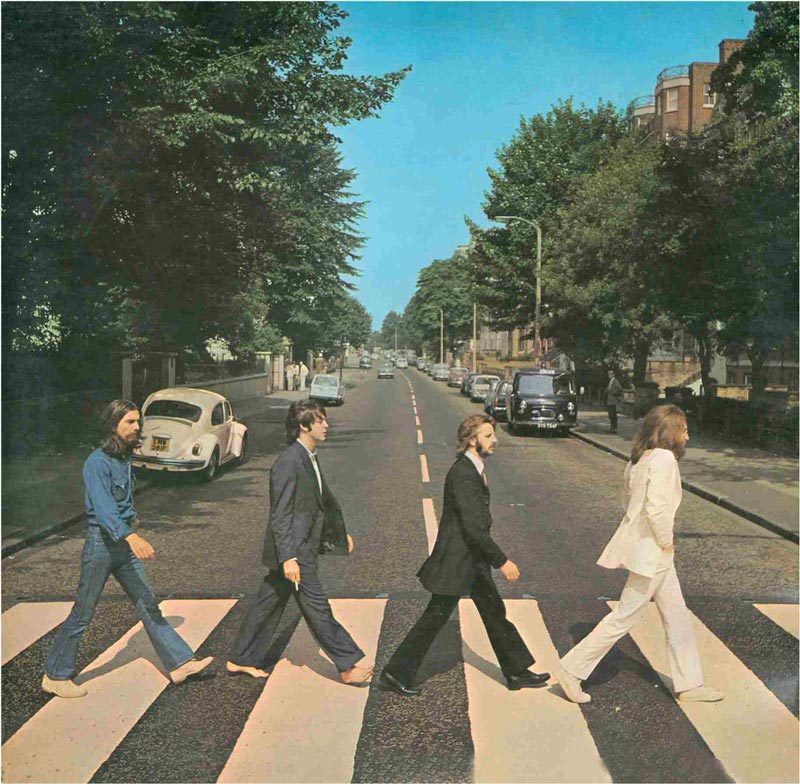

Do secular holy sites (Abbey Road comes to mind) testify to modern society’s yearning for transcendence? What about you? Where have you trodden on holy ground? Was the experience private or communal? Were the effects enduring or fleeting? How are you different?

- On the semantic range of huaca (location, spirit, energy, avatar, tomb), see R. Alan Covey, Inca Apocalypse: The Spanish Conquest and the Transformation of the Andean World (Oxford, 2020).

- Jacob Lassner, Medieval Jerusalem: Forging an Islamic City in Spaces Sacred to Christians and Jews (U. Michigan, 2017), 6-7.

- C. S. Lewis, Letters to Malcolm, Chiefly on Prayer (Harcourt Brace, 1963; HarperOne, 2017), chp.14.

- Claudia Brosseder discusses the overlap between indigenous veneration of huacas and Catholic veneration of saints, as well as Catholic efforts (e.g., the 25th session of the Council of Trent and the 3rd Council of Lima) to distinguish proper Catholic representation from pagan notions of embodiment, in “Cultural Dialogue and its Premises in Colonial Peru: The Case of Worshiping Sacred Objects” Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient 55 (2012), 383-414.

- The Sacred and the Profane: The Nature of Religion (1959), 23.