Cultural objects tell us who we are and what we value. They ground us in the past, wrap us into a community, and connect us to the spiritual world. They reassure and comfort, charm and celebrate. Cultural objects are the mirrors of humankind. — Nancy Moses1

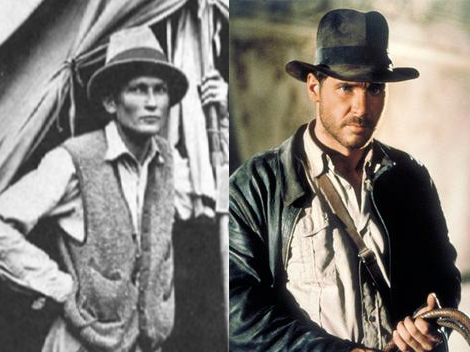

Bullwhip and Fedora

America’s favorite tomb raider is Dr. Henry (Indiana) Jones. We cheer the whip-cracking, fedora-sporting adventurer as he purloins a golden idol and evades an ancient temple’s death traps in the opening scenes of Raiders of the Lost Ark. Nor do we object when the National Museum curator agrees to buy Indy’s cache of stolen loot. After all, these artifacts freshly smuggled out of Peru would soon join the American museum’s venerable collection for the public to enjoy.

It’s fitting that Raiders would begin in Peru given that Harrison Ford’s character was indirectly inspired by Hiram Bingham, the early 20th c. Yale professor who rediscovered Machu Picchu and Vilcabamba (though he mis-identified both) and who, like Indy, exited Peru with a sizable stash of artifacts (cough, 400,000, cough) that wound up in the hands of his university (and which were returned to Peru only recently).

Digging for Cash or Culture

In Peru, tomb raiders are called huaqueros [wa-ke-ɾos], practitioners of what’s been called the “second-oldest profession”:

“Like the courtesan, the tomb robber knows there is money in beauty, and rarely a shortage of customers.”2

The beauties that huaqueros seek are ornaments, scepters, diadems, masks, weapons, amulets, textiles—whatever the ancient ruling classes left to honor and fortify their dead. But they prize these artifacts not for the light they shed on culture and history, but in order to flip them for profit.

They work by night like Indiana Jones in Egypt so as not to attract other looters, or even around the clock, and hastily sell their plunder through intermediaries to rich, mostly-foreign collectors.

By contrast, archaeologists—real ones—seek artifacts for the stories they tell us about people, about ancient civilizations: how a community lived, what they ate, with whom they traded, with whom they fought, how they appeased their gods. Unlike huaqueros, they are as eager to excavate adobe homes and simple workshops as gilded tombs and royal palaces.

Running out of Time

About 500 miles north of Lima not far from the Pacific is Sipán, known for Huaca Rajada, the tel that until the 20th century hid the secrets of Moche civilization. After the puzzling demise of the Moche 1,200 years ago, other peoples built upon their foundations until the rise of the Incas in the 15th century.

It was on this hill in February, 1987, six years after the debut of Raiders of the Lost Ark and seven years into the Shining Path insurgency, that five lucky huaqueros tunnelled their way into a mausoleum containing the remains of several generations of Moche rulers and their attendants.

“Addled on cane liquor and sucking coca leaves, the looters laughed and gasped in amazement as they pulled out gold and silver artifacts and filled up sacks with them. Within days they were selling the artifacts to middlemen, who began offering them to a select group of exporters and collectors.”3

Since the huaqueros ran out of time before their tunnels reached the greatest finds, it was archaeologist Walter Alva, doing post-huaquero salvage work, who got credit for unearthing the “richest unlooted funerary complex ever found in the Americas,” and the decorated human remains of one dubbed Lord of Sipán. From the late 3rd century CE, this Lord is “the first identifiable leader of Peru” and the “first known hereditary monarchy in the Americas.”

As one of the greatest archeological finds of the 20th century, Sipán draws comparisons with the tomb of Tutankhamen, the temples of Ur and the Dead Sea Scrolls. (68, 70). Indeed, as Atwood observes,

“more than any single site, Sipán helped move the geographical focus of the field away from the Mediterranean world, . . . and toward the indigenous societies of the Americas.”4

The artisans of ancient civilizations across Peru were endlessly creative. Some techniques evolved; some are largely unchanged. For close encounters with today’s guardians of Peruvian culture, consider these Curios experiences: mask making, ceramics, textiles, chullos, miniature animals, painting, and brick making.

To Retrieve is to Destroy

Huaqueros begin each search by driving metal poles into the ground, feeling for soft spots and voids, listening for telltale sounds. They dig with shovels and buckets, sometimes backhoes. Never subtle, never surgical. Always rushed and destructive.

They mutilate, violate, mangle, dishonor and discard their cultural heritage–whether tombs, kilns, canals, temples, even bones, flesh and hair. Only blackmarket valuables survive—that which acquisitive Americans and Europeans will pay to own: painted ceramics, jewelry, metalworks, especially textiles.

With a glut of ceramics on the antiquities market these days, pre-Columbian textiles are on every connoisseur’s wishlist. Textiles are also easier to smuggle since they don’t trigger X-ray machines. Pre-conquest weaves from Peru are like scrolls from the Middle East. (24) A colorful tunic travels quickly: to the US via Chile or Bolivia, or to Europe via Ecuador.

Archaeologists are destructive too, by the way. They don’t smash objects on purpose, but they do remove material, structures, walls, layer by tedious layer from topsoil down to the oldest remains. Unlike huaqueros, they don’t tunnel sideways. Their obsession with stratigraphy and with finding artifacts in situ, in their original location, is why they regard tomb raiders as the enemy. (31)

Knowing When to Stop

Archaeologists rarely excavate an entire site. It’s not just that funding is limited; they need time to write up and publish their findings. They usually leave most of the site for later generations of scientists who will resume the dig with better technology.

By contrast, huaqueros keep digging, braving dogs, police raids, cave-ins, even vigilant citizens’ patrols, as long as their metal-detectors continue to squawk, as long as sellable objects continue to appear. Some will pause to seek permission from the dead before ransacking their tombs, which formality is handled by a local shaman who makes offerings to the spirits of the huaca. (38) Permission granted, the race against time begins.

In Defense of Looting

Against their critics, huaqueros point out, correctly, that many ancient sites would remain undetected were it not for their honed instincts and tireless, clandestine labors. They might also champion their collectors for cherishing stolen pieces as art, in contrast to archaeologists for whom, they claim, the same items are mere objects of interest.(31)

Besides, they point out, foreign buyers preserve, protect and display treasures that might otherwise be lost, ignored or damaged in some cramped, underfunded museum in the country of origin. (46)

A similar logic animated the Earl of Elgin over 200 years ago when he did the Ottoman Empire a “favor” (evidently with their permission) in removing Athens’ Parthenon marbles, shipping them off to Britain and selling them to the British Museum.

They’ve lived there ever since, notwithstanding Greece’s multiple appeals, beginning in 1835, to repatriate their treasures, and the museum they recently built at the base of the Acropolis to receive them.

Comedian James Acaster exposes the entrenched colonial mentality that long justified such behavior, even as he demonstrates why such logic is no longer compelling.

Sunken Spanish Galleon

Recent campaigns to recover the patrimony of once-colonized territories like Egypt, Mesopotamia, Turkey, Greece and Latin America—campaigns sanctioned and abetted by the United Nations5—signal a cultural shift. It is past time for the West to acknowledge its collusion in cultural plunder. Foreign correspondent Sharon Waxman sees this shift as a battle for national identity, with ancient artifacts as the latest weapons:

“Is this historic justice, the righting of ancient wrongs from the age of imperialism? Or is it a modern settling of scores by the frustrated leaders of less powerful nations? And why now, all of a sudden, has the issue taken hold with such force? The battle over ancient treasures is, at its base, a conflict over identity, and over the right to reclaim the objects that are its tangible symbols. At a time when East and West wage pitched battle over fundamental notions of identity (liberator or occupier; terrorist or freedom fighter), antiquities have become yet another weapon in this clash of cultures, another manifestation of the yawning divide.”6

This modern quest for restorative justice, this national impulse to retrieve lost cultural heritage, is complicated.

Should we applaud a system that allows Peruvian collectors to retain possession of artifacts that were illegally extracted if they but register them with the Instituto Nacional de Cultura (INC) and pledge to keep them in country? (47)

How should we manage competing claims? In 2007 American divers in international waters found a Spanish galleon sunk in 1804 by the British, and with it $500 million of gold extracted from what is today Bolivia, Chile and Peru. To whom does the bullion belong? Is it finders-keepers for the American salvage company? Should Spain get to reclaim their ship’s cargo? Or does Peru have a case since the coins were evidently minted in Lima?7 (Spain won the case in 2012.)

Rubber Boots

None of this complexity exonerates the huaquero, who is guilty of mercenary acts of cultural destruction. Atwood sharpens the point:

“looting obliterates the memory of the ancient world and turns its highest artistic creations into decorations, adornments on a shelf, divorced from historical context and ultimately from all meaning.”8

We should not be surprised, however, nor too self-righteous when hardship leads to opportunism. Put yourself in the rubber boots of the huaquero. Would you feel protective of your country’s cultural heritage if your pockets were empty and you had mouths to feed, if you lived in rural isolation with few legal opportunities to get ahead? Would you feel obliged to play by the rules if 42% of your country’s economy was “informal,” i.e., untaxed, unregulated and unprotected by the government? What risks would you incur if your half of the population struggled with food insecurity?

If the elites above you—corporate, political, diplomatic—are themselves addicted to bribery and corruption, some of them profiting handsomely from the illegal antiquities trade, would you not be tempted to follow their example? Given astonishing wealth gaps and endemic corruption, tomb raiders have excellent motivation to stay in the game. Perhaps Nancy Moses is right that “all we might be able to do is to stop ourselves: the buyers.”9

Broken Promises

One might suppose that villagers on whose terrain the treasure was found would reap tangible benefits. Rarely is this the case. The Moche museum that opened in 2002, sure to attract tourists dollars and local jobs, was not built in Sipán but 20 miles away in Lambayeque.(257) Sipán locals have:

“almost nothing to show for it: no running water, no paved roads, no medical care to speak of, and no hope. After years of broken promises, the people of Sipán scowl and glare mistrustfully at visitors. . . . The villagers are poor, forgotten, and angry.”

No surprise, then, that struggling communities tend to regard local ruins as “curious but insignificant vestiges” of a distant past, and will, unless prevented,

“bulldoze, dismantle, or dynamite ancient structures to create space for the construction of reservoirs, roads, canals, and football fields. In Santa Cruz, such projects have replaced ancient stone canals with concrete ones to reduce water loss; removed ancient bench terraces that were once sowed with foot plows to make cattle and tractor plowing easier; and repurposed the stones of ancient house walls as construction fill for reservoirs. Though destructive to archaeological remains, these projects are important public works that symbolize ‘progress’ to many local people.”10

Atwood recalls the complaints of an elderly woman:

“‘They take those treasures all around the world, and what happens to us? We have to bathe in the irrigation ditches. First the horses, then the cows, then the goats, then us. . . The archaeologists come here and dig up all the gold and silver and leave us with nothing. And they call us the looters’.”11

Few tomb robbers strike it rich. Most live out their days in the menial classes. Middlemen and “mules” fare better, but most wealth accrues upward to antiquities traders domestic and foreign, paralleling the upward, inequitable flow of cash from Peru’s extractive mining industry.

Six hours east of Sipán brings you to Cajamarca where Francisco Pizarro held Atahualpa ransom and fueled Spain’s frenzy for Inca gold. How is it that Cajamarca’s mines have poured “nearly $1.5 billion of gold into the global market in a single year” while “three in four residents live in numbing poverty”? Why do we see beggars “sitting on a bench of gold”?12

Haunted by the Past

To set the illicit behavior of tomb raiders in historical and economic context is not to defend their crimes. It is simply to acknowledge that Latino campesinos have themselves been subject to exploitation, forced resettlement and enslavement over generations. The Inca elites abused them, as did the Spanish.

In our own day Latin American republics have “concentrated all power in a tiny elite, placed few restraints on their staggering clout, and invited the rest of the world in to exploit the land and its people.”13

Does this dark history of human exploitation continue to haunt Peru today? Absolutely, says archaeologist Walter Alva:

“Young men were willing to dig up the tombs of their ancestors and sell their contents to fatten private collections because they had been conditioned by centuries of indifference or disdain toward Peru’s indigenous heritage.”14

Part of the blame, say professors Bria and Carranza, lies with an educational system that has:

“disenfranchised these communities from their history by perpetuating a post-colonial, nationalistic narrative that all Peruvians are mestizo—mixed Spanish and indigenous race and culture.”15

So the fight to safeguard antiquities is in part a quest to “give pride and a sense of identity to Peruvians, a people in bad need of national self-respect.”16

For that quest to succeed it will also need heritage projects co-created by local communities and visiting researchers. It will cultivate indigenous self-respect through traditional festivals, oral history workshops, and artisanal co-ops that preserve and pass on Peruvian traditions.17 Archaeologists will want to encourage villagers to connect their distant and recent past.18

And even though so many of Peru’s antiquities reside overseas,19 we must cherish the ones within our country. Directly across the Urubamba river from our hamlet in Cusco’s Sacred Valley lives a remarkable private collection at Hacienda Huayoccari. Artifacts come from Tiahuanaco in Bolivia, Wari culture, the Inca Empire and the colonial period, all of which the family of Don José Orihuela delights to show their visitors. When you visit our Valley, you won’t regret it if you make time for this verdant oasis.

- Nancy Moses, Stolen, Smuggled, Sold: On the Hunt for Cultural Treasures (Rowman & Littlefield, 2015), chp.8.

- Karl E. Meyer, The Plundered Past, 1973, p.132.

- Roger Atwood, Stealing History: Tomb Raiders, Smugglers, and the Looting of the Ancient World (St. Martin’s, 2004), 12. Throughout this post a number in parenthesis points to related pages in Atwood.

- Atwood, Stealing History, 119.

- UNESCO adopted a convention in 1970 “against illicit trafficking of cultural property,” calling for “return and restitution.”

- Sharon Waxman, Loot: The Battle Over the Stolen Treasures of the Ancient World (Holt, 2008), 3.

- See Waxman, Loot, 8.

- Atwood, Stealing History, 9, 36. See also Angela Schuster, “Inside the Royal Tombs of the Moche” Archaeology (Nov/Dec, 1992)30-37, kindly shared by the publisher; Carme Mayans, “El tesoro del Señor de Sipán: el esplendor de los mochicas,” National Geographic (12-14-22); Santiago Uceda, “Investigations at Huaca de la Luna: An Example of Moche Religious Architecture” in J. Pillsbury, ed., Moche Art and Archaeology in Ancient Peru (National Gallery of Art, 2001), 46-67.

- Moses, Stolen, Smuggled, Sold, chp.8.

- E. Bria and E. K. Cruzado Carranza, “Making the Past Relevant: Co-Creative Approaches to Heritage Preservation and Community Development at Hualcayán, Ancash, Peru” Advances in Archaeological Practice 3 (3, 2015), 208–222.

- Atwood, Stealing History, 35-36.

- Marie Arana, Silver, Sword and Stone (Simon & Schuster, 2019), chp.5.

- Arana, Silver, Sword and Stone, chp.5.

- Atwood, Stealing History, 52-53.

- Bria and Carranza, “Making the Past Relevant,” 210.

- Atwood, Stealing History, 52-53.

- Many encounters and experiences available through CURIOS highlight the traditions (textiles, ceramics, food, drink) preserved by local artisans.

- Bria and Carranza, “Making the Past Relevant,” describe collaborative efforts in Hualcayán (District of Santa Cruz in Huaylas, Ancash), sponsored by The Proyecto de Investigación Arqueológico Regional Ancash (PIARA).

- Aldo Valerga, a reputable Lima collector, estimates that 80 to 90 percent of “all valuable, pre-Columbian Peruvian art ever created” is now to be found outside of Peru. See Atwood, Stealing History, 116.