Jesus’ awkward encounter with the Canaanite woman

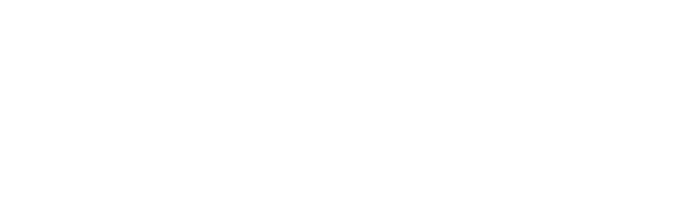

Jesus isn’t always nice. One time he pretty much called a Canaanite woman a dog, one with no standing or claims on him, a Jewish prophet. Two of the four New Testament Gospels (Matthew and Mark) describe the strained encounter.

These days, religious nationalism is getting a lot of attention. There’s Christian nationalism in the U.S.A., Hindu nationalism in India, and religious Zionism in Israel to name a few variations, but one encounters religious nationalism, exceptionalism, and tribalism at almost every port.

Was Jesus no different? Was Jesus tribal? Was Jesus a nationalist?

Over almost two decades I’ve spent lots of time in the Holy Land thinking about Jesus: Jesus healing the sick, Jesus telling stories, Jesus daring to announce the rule of God, and paying for it with his life. It’s not that being in the Holy Land answers all my Jesus questions, but it does help me ask better ones, and it reminds me that Jesus is neither Western nor modern. Left to myself, I’d prefer a Jesus who looks and acts like me, rather than face the real, Galilean Jesus whose behavior can make me uncomfortable.

Take the Jesus we find in Matthew 15 and Mark 7, for example. In Mark’s Gospel Jesus is on a retreat in Gentile territory. But Jesus didn’t go there to preach or to expand his support base; he was on a quest for solitude, which solitude is abruptly interrupted by a Gentile woman.

The Jesus of this story falls outside my comfort zone; he fails my Canadian politeness test. My imaginary Jesus would never respond to human need with silence. My Jesus would respond immediately with kindness and generosity. Especially to an anguished woman crying out in a man’s world, a helpless parent desperate to rescue a child in distress. Matthew’s Jesus, by contrast, resisted three times before finally agreeing to help.

Fixing Jesus doesn’t work

Modern interpretations of this awkward episode are often, shall we say, creative. Some would have us imagine a kind look on Jesus’ face. Maybe the woman saw a twinkle in his eye; he was teasing her, or testing her determination. Or maybe the tone of Jesus’ voice assured her of his benevolent intentions. Maybe, but this seems to me like wishful thinking. The woman is impressive here not because Jesus was subtly signaling to her that he wanted to help, but because she persisted when he wasn’t!

Another creative solution claims that the word dog isn’t really dog ; the word is puppy! Jesus was comparing the woman to a beloved house pet! This too isn’t interpretation, it is sentimentality. Most dogs in the ancient world were scavengers. They roamed the streets, pawed through trash, and ate whatever flesh they could find. Zero manners. And definitely not kosher. I can report that their descendants are alive and well in the villages of the Holy Land today.

The woman might have a house dog in mind, when she says that “the dogs under the table eat the children’s crumbs” (Mk 7:28). But this was her way of shifting Jesus’ metaphor in her favor; it reflects her humble resolve to do or say whatever it took to help her daughter. For Jesus to compare Gentiles to dogs was not a compliment. It subordinated them to the children of the household, the children of Israel.

Yet another creative approach to this perplexing text is to read the story as a parable. For Martin Luther it was about faith. He says:

“What a superb and wonderful object lesson this is . . . to teach us what a mighty, powerful . . . thing faith is. . . . By such tenacity and unflinching faith the Lord is taken captive and pressed to answer. O woman, … you . . . cling firmly to the hope that I will help you and you don’t let go of me. . . . May it be granted to you, even as you believe…”

Luther invites us to be like the woman in her persistence, her humility, her faith. Have your prayers ever been met with silence? Do you sometimes relate to old Habakkuk: “How long, O LORD, will I call for help, and you will not hear?” Then, says Luther, be like the woman. She bowed before Jesus (Mt 15:25). She called him Son of David. She called him Lord, three times! She persisted. And her prayers were finally answered.

Martin Luther is right about the remarkable faith of this tenacious woman, but unless we conclude that this historical encounter is really a parable, we haven’t solved our twin problems: Jesus was not eager to help the woman, and he likens her to a canine.

Rather than fix Jesus, I suggest we pay him closer attention.

Sheep or dog? (Hint: neither one is a compliment.)

First, it is clear that Jesus’ primary focus was on his own people. I might prefer a Jesus whose mission, from the beginning, was global. I might prefer a Jesus who went out of his way to encounter Gentiles, who stood against discrimination and tribalism. But here is where we need to let Jesus be Jesus.This Jesus is the prophet of Israel, convinced that his primary calling was to bring his people back to God, and away from injustice and unbelief. This Jesus is the son of David and King of Israel, charged with protecting and restoring his nation. This Jesus is the shepherd of Israel, burdened for his flock, lost and wounded as they were. Jesus is burdened to bring his wandering people out of exile.

Speaking of Jesus-the-shepherd, we should remember that while he compares Gentile outsiders to dogs, which is, ahem, awkward, he also calls his Israelite insiders sheep. Lost sheep. That isn’t a compliment either. Sheep are dumb, defenseless, easily led astray. Which is worse? Being called a dog or a sheep? One is foul, the other is foolish. One is wild, the other is weak.

This is the second time in Matthew’s Gospel that Jesus limits his mission to “the lost sheep of the house of Israel” (10:5-6; 15:24). Those sheep have gone astray; their shepherds have proven unfaithful; the good shepherd has come to bring them home. We like to multitask; Jesus resolves to do this one thing well.

Preview of Coming Inclusion

Second, notice that in the larger Gospel story, this awkward episode is actually good news for those of us of the Gentile persuasion. As it turns out, the border between favored insiders and neglected outsiders is porous, and would soon disappear. Did you notice what Jesus says in Mark’s verse 27? “Let the children first be fed.” Not only but first.

The Gospels include more than a few sightings of Gentile outsiders sneaking crossing the border (Mt 8:11). The Magi brought gifts to baby Jesus (Mt 2). Outsider Persians worship the child while insider Herod tries to kill him. Then there’s the Roman centurion whose servant Jesus healed. His faith was greater than anything Jesus had thus far found in Israel (Mt 8:10). Consider also the Samaritan woman at Jacob’s well. Her whole village who came to believe that Jesus was the Savior of the world (John 4). And that other centurion who witnessed Jesus’ crucifixion and called him the Son of God (Mt 27:54).

By the time Matthew and Mark were writing their Gospels, the church’s mission to the nations was roaring. The trickle of Gentile Jesus-followers was now a flood. And so, Matthew ends his Gospel with Jesus, the same Jesus who came for the lost sheep of Israel–this Jesus charges his disciples not to stay within the fold, but to go and make disciples of all the nations (Matt. 28:18-20). Times have changed. The Gentile woman up in Lebanon may have been an exception to the rule at the time, but she was a preview of coming inclusion, a harbinger of God’s blessing upon the nations.

Canaanite Lives Matter

Third, pay attention to the way this woman is described. Mark says she was from Syrian Phoenicia; Matthew calls her a Canaanite. Canaanite is a trigger word. Everyone, Matthew included, knew that the Canaanites were ancient Israel’s bitter enemies. They stood in the way of Israel inheriting the Land. They led Israel into false worship. They were the ultimate outsiders!

But here, in the New Testament, something has changed. The only time the word Canaanite appears in the New Testament, it refers to a woman of remarkable faith. No longer is the Canaanite someone to expel; now she is someone to welcome and emulate.

This Canaanite woman might remind us of other Canaanite women, especially Rahab, whom Matthew already mentioned as one of Jesus’ great, great, great grandmothers (Mt 1:5). Rahab was also desperate; she also feared for her family; she too took bold action; she declared her faith in the God of Israel; she persisted in asking for help; she persuaded the Israelite spies, all of them male, to grant her wish and save her family; she too received the mercy she asked for (Josh 6:22-25).

So, long before Jesus encountered a Canaanite woman, Rahab and other Canaanites had already found pathways across the border and taken refuge among God’s people. History repeats. Even the most notorious, suspicious outsiders–Canaanites–find room at the table of God’s grace.

A Woman Changed Jesus Mind

Finally, let’s not allow anxieties about Jesus’ harsh language blind us to the most surprising detail of the story. Nowhere else in the Gospels do we see Jesus change his mind.

The Gospels do not portray Jesus as static and inflexible. Their Jesus is not made of stained-glass; he is fully engaged with us and fully responsive to our pleas.

This woman seems to have persuaded Jesus that his rescue mission was not a zero-sum game, one in which Jewish gain could only come at Gentile loss. And the woman was right: there was no reason to think a Jewish prophet could not also bless Gentiles. There was every reason to think that Jesus could show compassion to Gentiles without diminishing his mission to Israel.

Bread enough for all

This woman challenged Jesus to let God’s abundant provision overflow. Jesus accepted her challenge.

Just before this episode in both Matthew and Mark, we see Jesus feeding a large crowd of hungry Jews (Mk 6), like Moses serving Manna in the wilderness. There were 12 baskets of leftovers. Immediately following our story, Mark tells us that Jesus went to a predominantly Gentile area (7:31) — the Decapolis — where he fed another hungry crowd. Again, lots of leftovers.

In between these two banquets we find the Canaanite woman assuring Jesus that there would be bread enough for all, and grace enough to more than satisfy Jesus’ family and foreigners too.

If the Canaanite woman helped Jesus see the full significance of his mission, she may also have a message for us today. She challenges us, like she challenged Jesus, to let grace flow, to cross boundaries, embrace outcasts, and attend to the cries of desperate women and afflicted children. I’m grateful to have friends, like Rev. Isaac Villegas in North Carolina, who have taken up that challenge.

Public discourse and social media these days are marked by fear, suspicion, contempt, and tribalism. The Canaanite woman reminds us not to hoard grace. We must listen for the cries of strangers and aliens, not just of family and friends. We must, she would say, extend hospitality and protection to the vulnerable, healing to the sick, and welcome to the stranger. The good news is that there is more than enough bread for all.