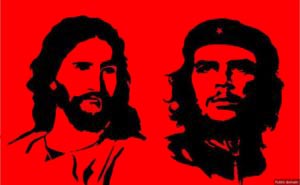

Was Che Guevara more radical than Jesus?

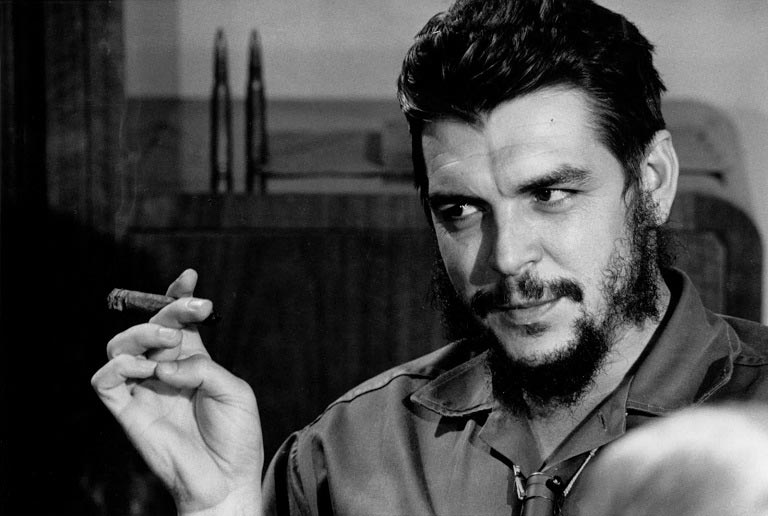

Jesus didn’t smoke cigars or ride motorcycles. He didn’t cross continents or play chess or excel at Rugby or earn a doctorate or write books. But after a recent visit to Cuba, I found myself comparing Jesus to cigar-smoking, motorcycle-riding Che Guevara.

I’m hardly the first to consider the ancient Jewish prophet alongside the Latin American Marxist revolutionary whose death in the turbulent sixties coincided with the birth of Liberation Theology in the work of Peruvian priest Gustavo Gutierrez. But wait. The parallels are impressive.

Both Jesus and Che traveled from village to village practicing healing arts with an eye for forgotten and marginal campesinos, one as a medical doctor, one as a wonder-worker; one in the Andean highlands, the other in the Galilean foothills. Both saw human need and responded with compassion. Both men turned to a second career; one shifting from medicine to politics and itinerant warfare, one from carpentry to prophecy and itinerant teaching.

Both men gathered and led a small band of improbable revolutionaries. Both men denounced those who wielded wealth and power to exploit and oppress. For both, the world needed liberation; for one it was from enslavement to capitalist overlords, for the other, from enslavement to the corrosive powers of this present age.

Both struggled for justice, but for others, not themselves. Both led by principled example, one loyal to Fidel and his revolution, one to God and his reign. Both men saw a better world coming, a time when fortunes would be reversed: the hungry would be filled, the mourners comforted.

Both cherished holy books; one loved to quote David and Moses, the other Marx and Engels.

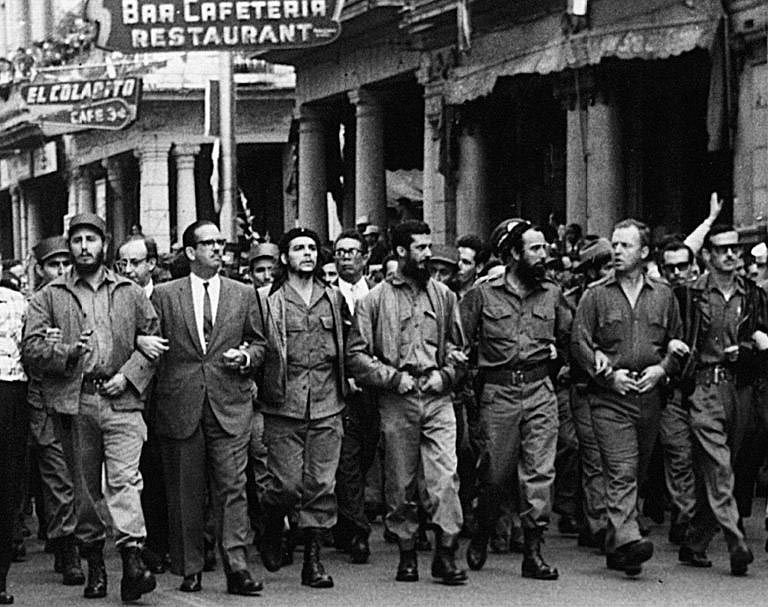

Both men campaigned in the countryside among peasants before launching an improbable assault on the capital city. One defied a US-backed strongman named Batista; the other (inspired by Juan el Bautista) challenged a Rome-backed strongman named Pilate.

After their arrest, both endured torture but were silent before interrogators. In their distress, one asked his captors for something to smoke, one for something to drink.

March 5, 1960, in Havana at a memorial march for victims of the La Coubre explosion.

Both men died painfully, violently in their thirties, executed by the superpowers of their day for crimes against the state. Rome’s appointed governor eliminated one insurgent, the CIA’s Bolivian designate dispatched the other. The hands of one were pierced with nails, the hands of the other were chopped off. Neither had a fair trial.

Both men have disciples around the world. Havana’s shops are as full of Che t-shirts and woolen berets as Bethlehem’s are of Jesus icons and olive wood carvings.

Each man’s disciples revere their sayings, study their lives, celebrate their virtues, mimic their deeds. For both bands of disciples, the death of their hero is more than tragedy and defeat. Pilgrims visit the sites of their death, feel their presence, offer up prayers. For some Bolivians today, Che is “Saint Ernesto.”

My hunch is that other Jewish revolutionaries would have earned Che’s approval: Judas Maccabeus for his guerilla tactics, Simon Bar Kochba for his brutal discipline.

Villagers in Bolivia

But for Jesus’ revolutionary vision Che had only disdain.

Che measured success in terms of mastery, not mercy.

Che took up the sword to combat the powers of his day; Jesus trained his troops to sheathe the sword.

Jesus turned the other cheek; Che countered violence with violence.

Soldiers spat in the face of Jesus; Che spat back.

Some of Jesus’ earliest disciples might have preferred Che’s approach to the one adopted by their Galilean comandante, the result of which was death on a cross, not killing with a gun. We are not surprised, then, when later followers of Jesus (like us?) struggle to love their enemies, or when the very idea of enemy love repulses people like Che.

I marvel at Che’s zeal for “the least of these” and admire his passion for justice, but after this, my first visit to Cuba (January, 2018), I departed thinking that the Argentinian rebel wasn’t revolutionary enough.