Are Crusaders still battling for Jerusalem?

They found the trench! This summer archaeologists went public about their discovery of a moat-trench, south of the Old City walls, that protected Jerusalem from the Crusader siege of 1099. According to ancient reports, a man of the church offered gold to soldiers who would venture under cover of darkness to fill in the trench — it was 17 meters wide — so that Crusader siege towers could approach the city wall to launch their assault.

Today, 920 years later, men of the church are still contending for Jerusalem, along battle lines that are equally clear. The good news is that these Christian soldiers glare across a hermeneutical moat, their siege towers are books, and their arrows are words. The bad news is that people are still getting hurt.

On one side of the trench are Christian Zionists who celebrate more than a century of Jewish migration to the Holy Land, not simply because individual Jews needed safe haven from reprisals, pogroms and antisemitism, but because God has given them the Land; because God is now at work; because biblical prophecy is being fulfilled; and because the regathered people of Israel have a central role to play in God’s plan.

Peering back across the divide are fellow Christians, Palestinians among them, who see no reason to privilege Jews over non-Jews in the Land. Jesus came to fulfill God’s covenant to Abraham, so that Jews and Gentiles are now co-equal heirs of the promises in the commonwealth of Israel. The modern Jewish state, largely the outcome of antisemitism, colonialism and nationalism, has been a catastrophe for indigenous non-Jewish inhabitants.

Rhetorical arrows fly in both directions. Holy hand-grenades detonate.2

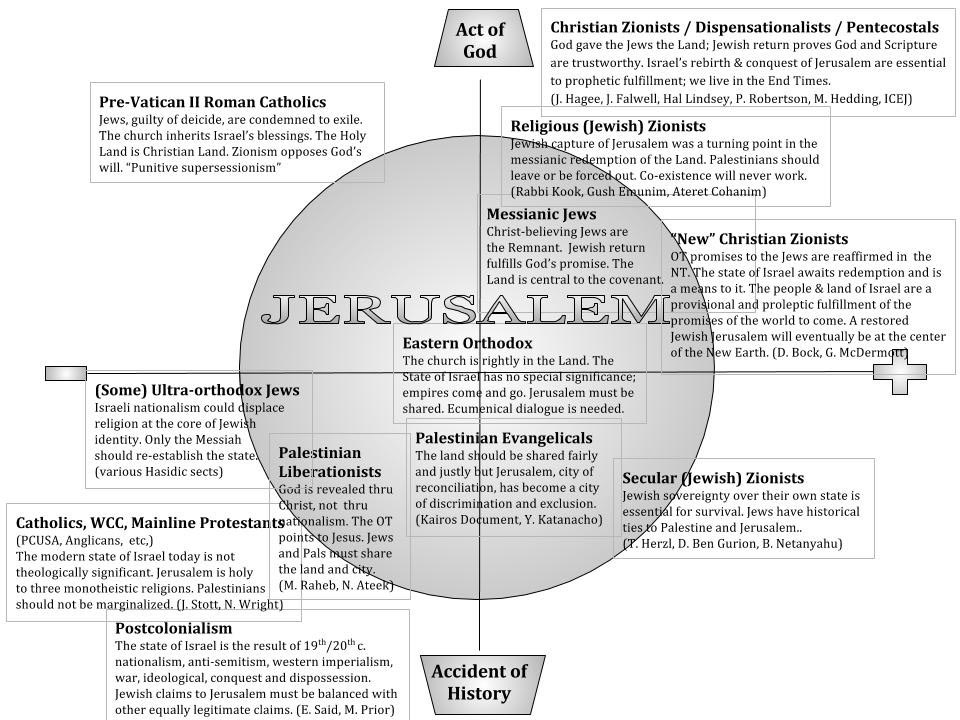

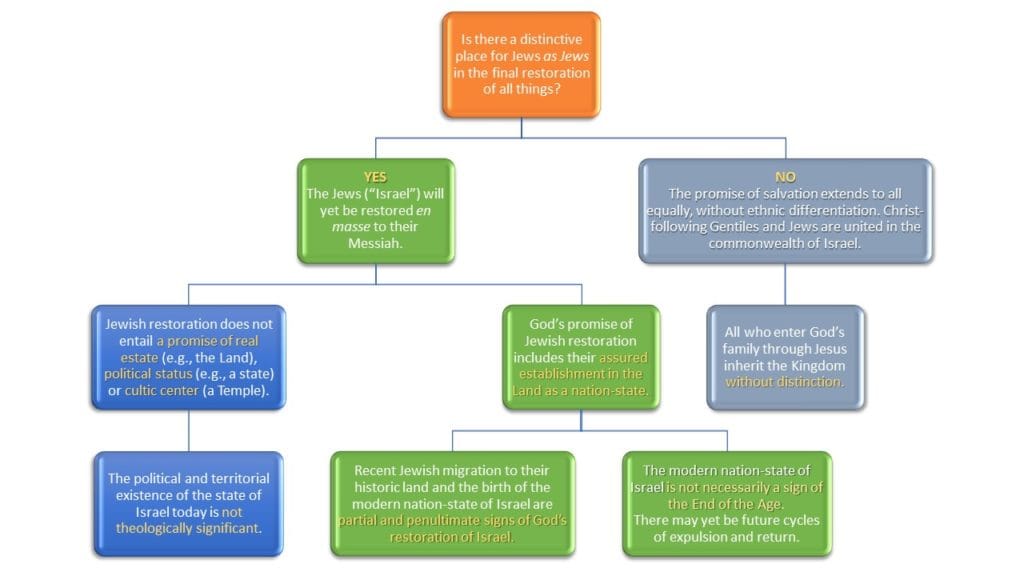

It would be wrong to conclude, however, that Christian ideas about modern Jerusalem could be reduced to a simple pro-con binary. Here’s a chart that attempts to show, inadequately, some of the messiness of the hermeneutical landscape.

X — whether or not one welcomes the Jewish capture of East Jerusalem

(and prior establishment of Israel)

Y — whether or not one sees the Jewish capture of modern Jerusalem as an act of God

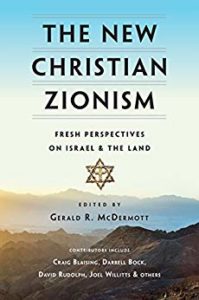

Christian Zionism 2.0

The rest of this post is about one group of combatants (look in the upper-right quadrant): the self-named “new” Christian Zionists. This predominantly American group hopes to distance itself from an older brand of Christian Zionism, still very much alive, that trades in global conspiracy, disappearing Christians, and conflagration on the plains of Megiddo in northern Israel.

In contrast to cliff-hangers and nail-biters like The Late Great Planet Earth and Left Behind, a recent book titled The New Christian Zionism, edited by Anglican scholar Gerald McDermott, is far too academic to be a bestseller or make it to the big screen. Rather than stoking fears of Armageddon, the authors want to stir up scholarly support for Israel and counter what they see as Israel’s increasing alienation. So: no end-times speculation, no breathless headlines, and no zeal for building a Third Temple.

Less alarmism and more scholarship. Sounds like progress.

Darrell Bock sums up the thesis of the project:

“Israel has a corporate future in God’s plan and as a nation has a right to land in the Middle East. Israel also has a right to function as a nation and be recognized as such in the world.”

The New Christian Zionism, 308 (emphasis added).

Likewise, Gerald McDermott assures us that the recent establishment of “ethnic, national, territorial Israel” is no accident. It is God’s doing:

“The return of Jews to the land and the establishment of the state of Israel are partial fulfillments of biblical prophecy. . . , part of God’s design for what might be a long era of eschatological fulfillment.”

New Christian Zionism, 14.3

Craig Blaising is equally clear that the birth of the modern nation state of Israel is an act of God:

“The modern restoration of Israel to national status after so long a dispersion . . . needs to be understood . . . as an act of God in continuity with the divine plan for (1) an ethnic, national, territorial Israel and (2) the nations of the world.”

Blaising, New Christian Zionism, 102.

This is what sets most Christian Zionists apart from Christians beyond the trench. For Christian Zionists, it is not enough to believe that many individual Jews will yet embrace Jesus as their Messiah. Jewish restoration will certainly be personal and spiritual, but it will also be corporate, territorial and political.

The green boxes in the chart below trace Christian Zionist thought. Paths in blue or grey show alternatives — paths taken by other Christians who attach little theological significance to Israel’s recent establishment as a nation-state and her current control of Jerusalem.

Battlefields are not conducive to dialogue.

These new Christian Zionists are on a mission — a hermeneutical, historical, theological, political combat mission. Their book is neither dispassionate nor disinterested in contemporary politics. When they broach the subject of political justice for Palestinians, they generally defend Israel’s behavior against her critics.4 When “new” Christian Zionists do criticize Israel’s track record — we are told that it is neither “perfect” nor above “criticism”5 — their remarks are abstract, devoid of specifics. In this respect, the difference between “new” and “old” Christian Zionism is negligible.

One hopes that as the movement evolves, it will engage more directly with the ideas of Palestinian Christians, conspicuously absent from this flagship volume, who are affected daily by the territorial claims and policies of “the nation-state of the Jewish people.”6

The only non-Jewish inhabitant of the Land to get airtime is Shadi Khalloul, an Aramean/Maronite Christian Israeli. But rather than speaking for Palestinian Christians under Israeli control, Khalloul distances himself from them7 and charges them with “dishonesty” for their “anti-Israel political conferences” at which they are “serving Islamic propaganda” — charges he draws from a tabloidesque exposé of the 2012 Christ at the Checkpoint conference (held in Bethlehem), prepared by the bombastic British pastor, Paul Wilkinson.8

Presumption of virtue?

Christ at the Checkpoint is a biennial, international conference in Bethlehem that explores “what it means to follow Christ in the shadow of walls and conflict.” It invariably draws criticism — some deserved, some predictable, some off the mark — for its organizers are audaciously attempting to forge an indigenous Palestinian theology in a very challenging context, under withering scrutiny. They are just as subjective and fallible as are the contributors to McDermott’s volume.

I don’t doubt the integrity of the authors if not fully persuaded by their arguments. Am I naïve to hope that these scholars would extend the same presumption of virtue to Palestinian Christians? And that Palestinians would return the favor? I shall be watching how “new” Christian Zionism evolves,9 and hope for a breakthrough, led by combat-weary soldiers who yearn for ceasefire and for a chance to break bread with Palestinian children of the Land. And I shall hope that Palestinian Christians accept the invitation. If they did, I predict the news would spread quickly. And all would see that there is wisdom on both sides of the trench.

It's your turn!

Is there common ground between the two sides in this hermeneutical battle?

What does the New Testament say about the importance of the Land?

Did Jesus come to abolish Judaism? To fix it? To start a new religion?

What role does the Land play in God’s future, as you understand it?

- (Der praktische Schulmann, Stuttgart)

- To feel the tension between pro- and anti-Christian Zionist camps, see David Parsons, “Swords into Ploughshares: Christian Zionism and the Battle of Armageddon” (ICEJ, n.d.), https://int.icej.org/swords-ploughshares (accessed 10-12-17). Less polarized assessments of the battle include Shalom Goldman, Zeal for Zion: Christians, Jews, & the Idea of the Promised Land (UNC, 2009); Gershom Gorenberg, The End of Days; Robert Smith, More Desired than Our Owne Salvation: The Roots of Christian Zionism (Oxford, 2013); G. Gunner and R. Smith, Comprehending Christian Zionism: Perspectives in Comparison (Fortress, 2014); Stephen Spector, Evangelicals and Israel: The Story of American Christian Zionism (Oxford, 2008); S. Munayer and L. Loden, Through My Enemy’s Eyes: Envisioning Reconciliation in Israel-Palestine (Paternoster, 2014). For a historical overview by a Christian Zionist, see Paul Merkley, Christian Attitudes Toward the State of Israel (McGill-Queen’s, 2001). Christian Century vol. 134, no. 18 (August 30, 2017) is devoted to “Theologizing about Zionism.”

- Cf. p.27: “the people and land of Israel represent a provisional and proleptic fulfillment of the promises of that new world to come. So Jesus brought a new era to the history of Israel . . . and he predicted that his people and land would be central to that new world.” Notably, Joel Willitts (p.139) is more cautious in his assessment of the modern state: “a judgment about the theological legitimacy of the modern state of Israel cannot be rendered with unqualified certainty.”

- See chapters by Robert Nicholson and Shadi Khalloul, as well as pp. 20-26, 307, 315, 326-28.

- See pp.12, 14, 29, 102, 288, 297, 299, 309, 313-14, 328.

- I’m thinking of people like Archbishop Elias Chacour, liberation theologian Naim Ateek, Latin Patriarch Michel Sabbah, peace activist Mubarak Awad, non-violence advocate Sami Awad and academics Munther Isaac, Alex Awad, and Jonathan Kuttab. Yohanna Katanacho and Salim Munayer appear in single footnotes with no serious engagement of their ideas. Bock notes the volume edited by Salim Munayer and Lisa Loden, a Palestinian Christian and a Messianic Jew respectively, The Land Cries Out: Theology of the Land in the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict (Cascade, 2012), but he doesn’t engage the book’s ideas, notwithstanding its conciliatory tone and breadth of perspectives, among them Palestinian Christian, Messianic Jewish, American evangelical, and Dispensationalist. Unacknowledged also is Munayer and Loden’s sequel, Through My Enemy’s Eyes: Envisioning Reconciliation in Israel-Palestine (Paternoster, 2014). Contributor Robert Nicholson cites Palestinian Lutheran scholar Mitri Raheb (pp. 259-60) but doesn’t address his complaint, which is less about the people Israel being “invented” and more about indigenous Palestinians being marginalized.

- See p.298. Note that Khalloul’s community does not see itself as Arab (p. 29).

- Khalloul’s source is a webpage that is no longer active, but Wilkinson’s material is available online elsewhere.

- See Darrell Bock’s helpful final reflections on pp.309-315, which should be read alongside Peter Walker’s summary of the dispute in The Land Cries Out, 335-347.