For nearly three years home has been the Peruvian Andes, in a farming village with no paved roads, beneath snowcapped peaks (here’s the view from our front door →) in the Sacred Valley of the Incas and not far from Machu Picchu.

Alessandra is an entrepreneur and polyglot from Lima; I’m a gringo academic who taught religion for years in California and the Middle East. Our learning curve, like the trails we climb, has been steep.

Not long after we arrived, I reflected on why the mighty Inca Empire fell so precipitously to Spain’s Christian soldiers, mostly in their twenties, and why we shouldn’t rush to explain that conquest as an act of God.

Lately I’ve been wondering how the cosmovision of my indigenous neighbors changed, and how it didn’t, when Inca nature-worshippers embraced, or adapted to, Christian monotheism, and when Inca priests were replaced first by Catholic friars and then by Pentecostal pastors.

Inca Hears the Voice of God

Francisco Pizarro was 54 years old on his third trip to Peru when he ventured inland, ascended the Andes, and arrived at Cajamarca, 9,000 feet above sea level. The year was 1532. With Pizarro were 168 armed entrepreneurs, whom we call conquistadors: sixty-two on horseback, the rest on foot, plus a handful of slaves. An unlikely band of ruffians, they made their ascent in order to confront Atahualpa Inca, ruler of the New World’s largest empire.

On a gamble, Pizarro lured the mighty Inca into the Cajamarca plaza. In Atahualpa’s train were some five or six thousand warriors, with perhaps fifty thousand more at the ready nearby.

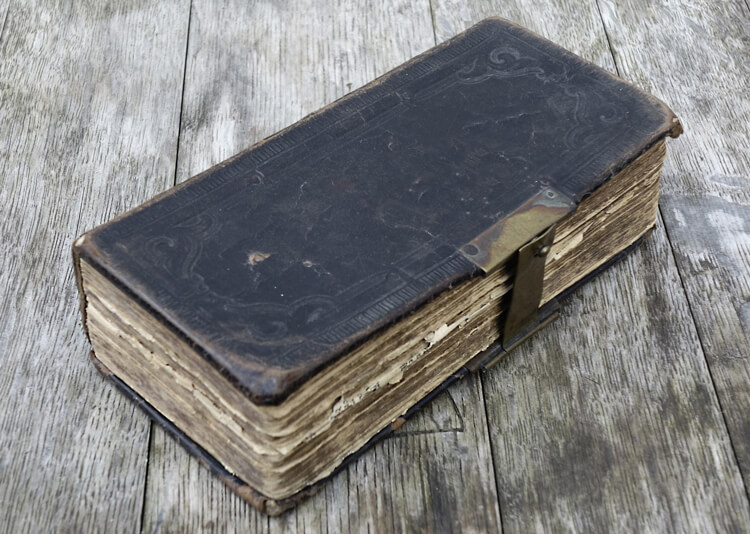

Huddling out of sight, Pizarro’s meager forces watched Dominican Friar Vincent de Valverde approach the Emperor with a book in his hands.

His task was to read the Requerimiento, a legal text of the Spanish monarchy composed twenty years earlier, that demanded foreign peoples’ abject surrender and submission to Spain’s King, Charles V, and to the Christian God, and that threatened all who resisted with total war, enslavement and death.

We don’t know how capable was Felipillo, the young translator—some religious jargon must have been unintelligible—but when Friar Valverde assured the Inca that the words of his declaration came from the book in his hands, indeed that this book contained God’s own voice, Atahualpa became curious and asked to see it.

Hiding Behind Marks on a Page

What book it was isn’t entirely clear. In the earliest account, eyewitness Cristóbal de Mena called it our holy law book. Pizarro’s notary public Francisco de Xerez said it was a Bible. An indigenous account by Tito Cusi Yupanqui, 38 years after the fact, called it God’s writing. Someone else (Garcilaso de la Vega) later said it was St. Thomas’ Summa and still later (Guaman Poma de Ayala) that it was a breviary or prayer book.1

Whatever it was, it was as sacred to the Christian Spaniards as it was inscrutable to Atahualpa, who had never held any book and didn’t know how to open it. He held it to his ear, heard nothing, and threw it to the ground, his confusion surely similar to what washed over Kaguvi, the hunter in Yvonne Vera’s African novel who, when watching a missionary priest reading a Bible, felt “pity for a god who has to manifest himself in this humble manner.” Like Kaguvi, Atahualpa could not understand “why a god would hide behind the marks on a page.”2

Empire Beheaded

The defiant gesture of a confused Atahualpa horrified the friar. He, along with Pizarro’s lurking conquistadors, knew that divine judgment would ensue for the barbarian’s desecration of their Sacred Book. God, after all, was on their side.

No surprise then that a brief two hours later “the Inca Empire had been beheaded,” as anthropologist Kim MacQuarrie puts it. For Pizarro, God had intervened.3 The improbable Spanish conquerors had captured the divine Inca, killed thousands (for the twin causes of God and survival), and seized a sizable portion of his 2,500 mile-long empire with its 10 million subjects.

Before long Spanish Catholics were erecting churches upon the foundations of Inca temples, and consolidating an imperial dominion that would endure until the 19th century. Thus it was that the mighty Inca Empire fell, and the Christian Empire spread, when the Holy Book spoke.

Talking Book

Fast forward 450 years. Skip over centuries of Spanish colonization, hard fought Peruvian independence, waves of terrorism, government scandal and corruption, and surges of economic development. In our day a Holy Book may again be challenging the powers that be and undermining the venerable religious establishment. This time, however, the Book is borne not by a Catholic friar but by a Pentecostal pastor. And the threatened establishment is not a pagan empire but the Catholic church, the very legacy of Francisco Pizarro’s conquistadors.

They worship the God who inspired the Bible, to be sure, but the Bible itself, almost personified, seems to wield its own power.

Of the fundmentalist and Pentecostal-influenced churches I’ve observed here in the former Inca stronghold, many congregations are strikingly biblio-centric. To be sure, they worship the God who inspired the Bible, but for them the Bible itself is virtually personified, and seems to wield its own power. The very words on the sacred page are “living and active,” to borrow from the book of Hebrews. They are fully authoritative and perpetually relevant.

Preachers in the pulpit thus hold the Bible aloft. They point to it, cradle it. For them and for their flocks, the Book is not only sacred. It is potent. It contains all that they need to live godly lives in a fallen world, as if human reason and experience, along with centuries of religious tradition have no place.

What’s more, these folk actually read their Bibles—much more, it seems, than many parishioners of nearby Catholic chapels, not to mention far away theology-lite, production-heavy churches in the Global North. When the preacher introduces a biblical passage, he waits for his people to find it, which they do without consulting the Table of Contents. Sometimes he invites the congregation to read verses responsively, back and forth; sometimes he pauses mid-sentence so the faithful can finish what he started, which they do readily because they’re following along or because the verse is committed to memory.

The Roman Catholic faithful in the Andes don’t generally bring a Bible to church, much less a full-sized study Bible wrapped in a sturdy-but-worn customized cover. For the still-majority Roman Catholic church in Peru, the Bible is neither God nor a God-substitute. Nor for Rome is the Bible “clear and revelatory to anyone who chooses to read it,” as the Reformation cry of sola scriptura might seem to imply.4

Christian Huaca?

Catholic missionaries complained early and often about Andean syncretism, the myriad ways their pagan converts smuggled elements of Inca religion into Christian faith and practice. Spain’s Christianity may have overwhelmed and superseded indigenous Andean religion. But that did not prevent Andean peoples from adapting it to make it their own.

Thus, the Andean pantheon embraced the holy trinity and Christian saints. The divine feminine Pachamama or Mother Earth fused with Mother Mary. Catholic feast days adapted the Andean ritual calendar. And Incan huacas—sacred springs, standing stones, mountains and caves charged with power and worthy of worship 5 —if not demonized and destroyed by the church, became sites for venerating the cross.

Is there analogous syncretism among Andean Protestants? How are today’s indigenous neo-pentecostals shaped by their Inca heritage? Could it be that the personified, vivified, talking Bible of certain Protestant communities has borrowed some of its features from the sacred architecture of the Incas? Is it fair to say that their Bible is not merely a book of inspired and authoritative sayings but itself a localized spiritual force, worthy of near-veneration for its power to establish moral boundaries, resolve disputes, banish doubts, and offer prophetic certitude?

Is the Bible, in other words, a Christian huaca?

My friends in these mountain communities would deny that their religious devotion focuses too much on the Bible, deny that they have elevated a sacred object over a Person. Perhaps they are right. But if these conservative, high-altitude Andean Christians do tilt toward bibliolatry, we find similar inclinations at sea level and across the globe, far from the influence of the Inca cosmovision.

Do not Christians who fixate upon the Bible miss out on a chorus of other voices, like history, tradition, human reason, scholarship, creation, experience, communal discernment, and the breath of God moving among us?

- Cristóbal de Mena, La Conquista del Perú. Joseph Sinclair, ed. New York Public Library, 1929 [1534], 10; Francisco de Xerez, La Verdadera relación de la conquista del Perú. Madrid: Historia 16, 1985 [1534], 111; Tito Cusi Yupanqui, Instruçion del Ynga Don Diego de Castro Titu Cusi Yupangui para el muy ilustre Señor el Liçençiado Lope Garçia de Castro, Governador destos Reynos del Piru. Lima: Ediciones Virrey.1985 [1570], 2; Garcilaso de la Vega, Historia General del Perú. Ed. Angel Rosenblat. Buenos Aires: Ed. Emecé, 1943 [1615]. I: 63, 73; Guaman Poma de Ayala, Nueva corónica y buen gobierno. Eds. John Murra and Rolena Adorno. México: Siglo Veintiuno.1980 [1609], 357. See further Bill Mitchell, “The Bible in the History of Peru: a study in the history of ideas” (United Bible Societies, n.d.).

- Yvonne Vera, Nehanda (Baobab, 1993), 104.

- Kim MacQuarrie, The Last Days of the Incas (Simon & Schuster, 2006), chp. 4. Also, R. Alan Covey, Inca Apocalypse: The Spanish Conquest and the Transformation of the Andean World (Oxford, 2020), chp.5.

- Peter Gomes, The Good Book: Reading the Bible with Mind and Heart (PerfectBound, 1996), 40.

- On the semantic range of huaca (location, spirit, energy, avatar, tomb), see R. Alan Covey, Inca Apocalypse: The Spanish Conquest and the Transformation of the Andean World (Oxford, 2020). On the overlap between indigenous veneration of huacas and Catholic veneration of saints, and on Catholic efforts (e.g., the 25th session of the Council of Trent and the 3rd Council of Lima) to distinguish proper Catholic representation from pagan notions of embodiment, see Claudia Brosseder, “Cultural Dialogue and its Premises in Colonial Peru: The Case of Worshipping Sacred Objects” Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient 55 (2012), 383-414. On the function and potency of huacas in the Andean imagination, see Claudia Brosseder, The Power of Huacas: Change and Resistance in the Andean World of Colonial Peru (U. of Texas, 2014).