Sacred Celestial River

South of the equator, the Milky Way tracks directly overhead. Northern-hemisphere stargazers are understandably jealous.1 No surprise that this galactic wonder fired the Incan imagination across an empire that spanned some 2,500 miles tip to toe, from 9 to 35 degrees latitude south. Think Roman Empire from Great Britain to Iran.

For the Incas, the Milky Way was a sacred celestial river—willka mayu in Quechua. When that river’s orientation dipped into the cosmic ocean upon which the earth floated, it drew waters into the sky that returned a s rain to renew the earth. The Milky Way thus continuously recycled water as “the principal organizing unit in the Andean astronomical-cosmological system.”2

To explore the night sky in the southern hemisphere, and learn about the importance of astronomy for the ancient Inacs, plan to visit Cusco and the Sacred Valley.

In Cusco, don’t miss the Dome Astronomy Workshop where you’ll watch the constellations dance. In the Sacred Valley, astronomer Fernando opens your eyes to the Andean heavens with fascinating insights and a huge telescope.

Creatures in the Night Sky

Looking toward our galaxy’s center, the Incas saw countless points of light, as do we. They also saw fields of darkness where no stars shone, something we are less likely to notice. If astronomers today explain these shadows as clouds of interstellar gas and dust, their Incan counterparts had a different explanation. They saw dark constellations—spirit shapes, powerful and influential, that mirrored creatures here below: two birds, two llamas, a serpent, a toad, a fox. Animals and birds on earth had supernatural heavenly counterparts.

I say the Incas were onto something. When we study our galaxy on a moonless night, we see patches of emptiness. Pondering the same canopy, the Incas saw fullness. Not a dark void or an unfortunate obstruction, but an animated presence. One of the shadows they beheld was a serpent that would herald the rainy season, corresponding to snakes on earth who emerge from their dens when the rains arrive. Another shadow was a celestial toad who would rise above the horizon at the very time of year that earthly toads end their hibernation and begin to mate.

The most conspicuous dark constellation in the southern sky is the llama, cherished Andean creature, beast of burden, source of meat and wool and fertilizer. The heavenly llama rises progressively higher in the wee hours during the earthly llama’s birthing season, from late November to April.

So the cosmovision of the Incas gives attention to darkness as well as light. To absence as well as presence. One might say they attended to negative space.

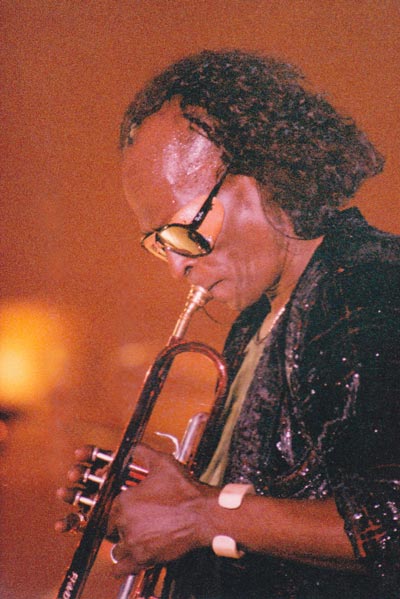

The Notes You Don’t Play

The importance of negative space is obvious to good musicians. For jazz giant Miles Davis, it was not the notes you played; it was the notes you didn’t play. Listen to the distilled simplicity of Broken Coastline by Caitlin Canty and Peter Adams. Sonic spaces between the notes emulate the empty, open road of which Caitlin sings.

Interpret the Page, Not Just the Ink

So too, good readers attend to the empty space between the lines. Conspicuously absent in biblical narratives—about, say, Abraham, Joseph or David—are words of explanation, motivation, description. Even God is under-described. As Meir Sternberg observes about the opening lines of Genesis,

“God comes on stage with a complete absence of preliminaries. Who is God? What is God? Where does he hail from? How does he differ from other deities?”5

“The sparely sketched foreground of biblical narrative,” Robert Alter notes, “somehow implies a large background dense with possibilities of interpretation.”6 Attentive readers become “partners in creating the story.”7 They strive to close narrative gaps and resolve ambiguities. They interpret the page, not just the ink. So the Incas teach us that darkness need not mean emptiness. Musicians, that unplayed notes are key to good performance. Writers, that gaps make good literature. As it turns out, every human endeavor needs seasons of rest. Every friendship needs periods of separation. Even the café barista knows to “leave room” for cream.

The Darkness of God 8

Emptiness is harder to celebrate when the missing element is God, when the light of Transcendence grows dim. Looking heavenward, Isaiah the prophet cried, Verily thou art a God that hidest thyself.9 The pain in his prayer is palpable:

O that you would tear open the heavens and come down, so that the mountains would quake at your presence . . . for you have hidden your face from us.10

The psalmist likewise laments, how long will you hide your face from me?11 Job dared to accuse: I cry to you, and you do not answer me.12 Even Jesus complained of divine absence. In agony on the cross he cried, My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?13

Theists and mystics alike acknowledge the darkness of God—those times when God seems absent in the face of gratuitous suffering and injustice, when luminescence is overtaken by shadow,14 when holiness dissipates. Riffing on Isaiah’s lament, theologians call this Deus absconditus. God hidden. It’s part of who God is, they assure us. God dwells in light inaccessible hid from our eyes.15 “God is outside and beyond our ideas of God,” says Fleming Rutledge. Omnipotence doesn’t perform on demand.

Saint Teresa of Calcutta knew well both human suffering and divine darkness:

Lord, my God, who am I that You should forsake me? . . . I call, I cling, I want—and there is no One to answer—no One on Whom I can cling—no, No One.—Alone. The darkness is so dark . . . The loneliness of the heart that wants love is unbearable. . . . My God—how painful is this unknown pain.16

Some people would weigh divine elusiveness as evidence for non-existence, or as reasonable warrant for disbelief. Others understand it as a sign of human estrangement. Mother Teresa and Jesus (along with many biblical authors) saw God’s inscrutable hiddenness as grounds for lament. All agree that the darkness of God raises questions that linger beyond the edge of our understanding. To which the Incas would respond: for those who have eyes to see, even in the absence of light, heaven may yet be charged with life.

- Astrophysicist Becky Smethurst explains why the Milky Way is more visible below the equator.

- Gary Urton, At the Crossroads of the Earth and the Sky: An Andean Cosmology (U. Texas, 1981), 60.

- See chapters 2 and 3 of William Zinnser, On Writing Well (1976, 6th ed., 2001).

- George Orwell, “Politics and the English Language” (1946).

- Meir Sternberg, The Poetics of Biblical Narrative (1985), 322.

- Richard C. Steiner, “Contradictions, Culture Gaps, and Narrative Gaps in the Joseph Story.” JBL 139 (3, 2020): 439–458, p. 445.

- Borrowed from Michael C. Rea, The Hiddenness of God (Oxford, 2018), 13.

- Borrowed from Michael C. Rea, The Hiddenness of God (Oxford, 2018), 13.

- Isaiah 45:15, KJV.

- Isaiah 64:1, 7 NRSV.

- Psalm 13:1, NRSV.

- Job 30:20, NRSV.

- Mark 15:34 NRSV.

- Fleming Rutledge, “Divine Absence and the Light Inaccessible” The Christian Century (8-27-18).

- From the hymn Immortal, Invisible, God Only Wise by Walter Chalmers Smith (1867).

- See Rea, Hiddenness, 3; cf. 18-19.